Moldmakers Are Increasing Business And Profits with Aerospace Work

Expertise in metal fabrication and machining creates opportunities for mold shops seeking diversification.

More moldmakers are prospecting for business outside their traditional markets to get away from outsourcing, offshore competition and the relentless price pressure of many jobs. One area where they’re finding demand for their fabrication capabilities, engineering expertise and problem-solving skills is in aerospace.

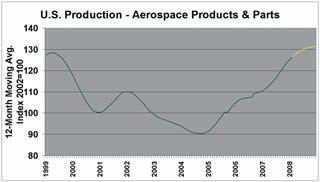

The timing couldn’t be better. Forecasts call for ongoing demand in civilian and military aircraft orders. Boeing, for example, predicts there will be 28,600 deliveries worldwide of new passenger airliners and freight aircraft by various manufacturers from 2008 to 2026, a buildup that some experts value at around $2.8 trillion.

Featured Content

Military programs are also strong, as countries seek to modernize and expand their fleets. One recent example of the economic benefits these programs provide, is the U.S. Air Force’s decision to award a team led by Northrop Grumman Corp. a $35-billion contract for 179 tanker aircraft. The winning design, dubbed KC-45A, is projected by Northrop Grumman to create 48,000 direct and indirect jobs at 230 U.S. suppliers in 49 states. Boeing, the loser in the competition, is challenging the decision, but however the ruling goes, the program will create a lot of business.

Little-Known Opportunity

Most mold shops, though, are unaware of the potential aerospace offers. “It’s an industry that not many people know a lot about,” says Melissa Millhuff, Executive Director of the American Mold Builders Assn. (Roselle, IL).

But for those mold shops that pursue the market, efforts are paying off. “Several of our members have moved into aerospace and are doing quite well,” notes Robert Dumont, President of the Tooling, Manufacturing and Technologies Assn. (Farmington Hills, MI).

Many of the moldmakers going into aerospace do so because the industries they built their businesses on are not generating enough work or profitability. The most problematic, Dumont notes, is automotive.

“The automotive industry has been devastating manufacturing in America by outsourcing as much as it does to Asia and elsewhere,” he says. “Moldmakers are so beaten down by pricing strategies among the auto manufacturers and their suppliers that staying in the business is one thing, but making enough profit to keep their doors open is a completely different matter. The more progressive mold shops are looking around to see what the alternatives are. Those that recognized the trend several years ago have been successful in moving on to other areas.”

The price of entry in aerospace is low: Toolmakers in most cases can rely on current equipment and capabilities when bidding for work. The metalworking skills and advanced machining capabilities that are the core of mold-building operations are key factors in winning jobs. And unlike many orders for injection molds, toolmakers usually invest little of their money upfront in aerospace jobs and generally receive payment soon after delivery is made.

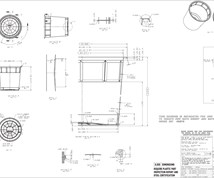

Most aerospace work for moldmakers involves building open and closed molds for composite materials and machining large and small components from metals like stainless steel, aluminum, titanium and Inconel, a nickel-based alloy. Moldmakers can also apply machining skills to composite parts, which need trimming before integration into an assembly.

Composites, especially advanced materials like epoxy and carbon fiber, are now a mainstay of aerospace design due to such properties as low weight, high strength and corrosion resistance, and can be machined on metalworking systems. (For a report on opportunities in machining composite aerospace parts, see MMT, December 2007, page 39.)

While an advanced capability like 5-axis machining is a plus for metal and composite parts, moldmakers say a lot of aerospace work can be done on 3- and 4-axis systems and on multi-axis wire EDM. What counts is accuracy, especially since aerospace tolerances are generally much tighter than in other markets—down to 0.0001 inch for some jobs.

“Five-axis machining is not absolutely essential—what’s most important is the quality of the part,” says Saleem Muneer, President of Catalyx Engineering LLC (Anaheim, CA).

ISO Meets Most Needs

Moldmakers typically work as subcontractors to Tier 1 suppliers. Aerospace OEMs, like their automotive counterparts, want to receive modules for assembly from a few suppliers rather than manufacture an aircraft from the ground up with components from hundreds of suppliers. Mold shops may not, consequently, need the range of quality certifications a Tier 1 or an OEM must have. While ISO certification is desirable, most toolmakers advise against applying for aerospace certifications like AS9100, a quality management standard that is complex, lengthy and expensive to acquire.

If a moldmaker develops an ongoing relationship with a Tier 1—or an OEM—and gets involved in critical fabrication work, toolmakers say it’s worthwhile to apply for higher-level quality certification. “But it’s a pretty involved process,” says Dan Glass, Director of Sales at Strohwig Industries (Richfield, WI), a moldmaker that recently expanded into aerospace. “There is a lot of paperwork, and you pretty much have to hire someone dedicated to monitoring the process for a year.”

Toolmakers say there is no size requirement on the part of mold shops for aerospace work. Small companies can compete as effectively as large firms, provided they have the equipment and fabrication skills, and deliver products on time and on spec.

One requirement, though, is a talent for problem-solving. Moldmakers say that as in any new industry, there is a learning curve in aerospace, especially since many of the metals in use are more advanced than the P20 and 1040 steel grades mold shops typically work with. And when it comes to building tools for composites, moldmakers must understand the shrink rates and other properties of the materials, which are substantially different than those of thermoplastics.

“We sat down with every part we worked on and analyzed what we’d done and how we could have done it better,” says Roger Roth, CEO and Marketing Director of Lunar Industries (Roseville, MI), about the company’s initial aerospace work. “The secret was to get our people thinking differently because we had been 100 percent in automotive. It took a while, but we learned how to do it.”

Most moldmakers say they get leads by networking at trade shows and conferences, and even by contacts from suppliers they worked for on jobs in different industries. Once a shop establishes a reputation for reliability and quality, word-of-mouth is an important route to new business. Price is, of course, a consideration in awarding aerospace jobs, but many suppliers pay attention to a mold shop’s ability to successfully deliver work, and to its record with customers.

“The aerospace companies are demanding,” says Roth, “but it sets us apart from competitors when a company chooses us for a job. We’ve won no-bid contracts from aerospace customers because they thought we were the only company that could do the work.”

Automotive to Aerospace

Lunar Industries began working in aerospace in 2000 by chance, though Roth had been thinking about the market. A client showed engineers at the company blueprints for an aerospace component it supplied, and asked if the mold shop would bid on it. Lunar’s engineers turned down the business, saying aerospace wasn’t their specialty. Roth says he thought about the decision and reconsidered. “We took another look at the part and decided we could do it,” he says. “We quoted it, and landed the job.”

Lunar produced the part, but lost money on it. “Making it was a real learning experience,” Roth says.

One reason for the problems was that the part, which Roth declines to identify, citing a confidentiality agreement, was made of Inconel alloy. “The material kept moving on us after machining, so we had to go back and remachine it.”

Roth is referring to a phenomenon known as “work hardening,” the tendency of Inconel to deform beginning with the initial pass of a machining tool. There are various ways to remedy the problem. In Lunar’s case, “We figured out that we could build a fixture to hold the material so when it was being machined it would relieve the stress itself—and the idea worked.”

Although the first aerospace job was a money-loser, Roth says the company has done well with every job since. Importantly, aerospace has given Lunar more consistent and profitable business than automotive, which accounted for 100 percent of operations in 2000.

Lunar no longer does automotive, a business Roth doesn’t miss. “Automotive is pretty much price. The customers want a lot of market value for the money, but all they look at is price,” he remarks. “They demanded that we become ISO certified, but then we found out they were taking the work to non-ISO companies offshore and to a few here in the states because they were cheaper.”

When asked what might have happened if Lunar had remained in automotive, Roth is blunt: “We’d be out of business.”

The timing of Lunar’s move was impeccable. “It’s important to get started in aerospace before you have to,” Roth advises. “We were swamped with automotive work when we said let’s go after aerospace, which was one reason why our people weren’t keen on it. You have to be thinking a couple of years ahead. You can’t wait until you have to have the work to make the transition.”

Cashing In with Machining

Strohwig Industries has been involved with aerospace for three years, and the market accounts for 10 percent of business, most of that in machining of large parts like weldments, castings and forging dies, which can be 20 to 40 feet long. The company expanded for much the same reason as Lunar Industries did. “We were trying to get a new niche,” says Glass. “Building injection molds is a cutthroat business; it’s hard to make a buck. Aerospace was something we wanted to try, and it’s worked out.”

The company still builds injection molds for a number of markets, among them, automotive, lawn and garden, housewares and cutlery. But its work in aerospace has boosted its custom machining business in other areas. “That’s probably another 20 to 30 percent of our business. We work in a lot of energy markets—windmills, big generators and natural-gas pumping equipment.”

Glass says that the economics of machining are much better than for moldmaking. “We don’t have to put money up front. With injection molds, you’re pretty much working for free for a good part of a project, since you buy the hot runners and other components. But with machining,” he notes, “the customer supplies the casting or the material. We machine it, send it out and get paid a week later. With molds it can take six months to get paid.”

Glass says demand is such that some customers have reserved machining time a year out. The company has in the last two years purchased six 5-axis horizontal machining systems with 35 to 50 feet of travel, and some smaller vertical units. The large machines each cost $2-3 million, and Glass says business has been strong enough for Strohwig to recoup the cost of each unit in 1-2 years.

Startups are also finding opportunities in aerospace. Alpha Machinery & Technology Co. (Sun Valley, CA) has been in business for a year. Formed by Edmond Nikoghossian, a moldmaker for 12 years, Alpha only machines parts. Nikoghossian says his experience with machining systems and related equipment suits aerospace work. “It’s not too hard for moldmakers to make the transition.”

Alpha does surface finishing on a 4-axis machine. Nikoghossian’s plans are to expand his shop and acquire machining systems that can fabricate high-precision parts.

Ripple Effect of Diversifying

Most mold shops have the skills and capabilities to compete effectively for aerospace work. Expanding in this area will increase business and firm up margins, and provide a shield against cyclical downturns in conventional mold-building markets. Aerospace is also cyclical, but will for the foreseeable future offer major opportunities to mold shops that leverage their experience in toolmaking and machining.

It will also create a ripple effect of job opportunities in high-growth industries like energy that require the same fabrication skills.

“The reality is if you keep doing the same things you’ve been doing, you’ll get the same results you’ve always been getting,” Dumont says. “At some point you need to raise your head up and say there must be a better way.”

RELATED CONTENT

-

How to Optically Polish Aluminum

There are two methods for optically polishing aluminum - knowing the right one for your project will save you time and money.

-

Choosing Between Cold and Hot Runner Systems

Get all the facts before selecting a runner system solution.

-

Predictive Manufacturing Moves Mold Builder into Advanced Medical Component Manufacturing

From a hot rod hobby, medical molds and shop performance to technology extremes, key relationships and a growth strategy, it’s obvious details matter at Eden Tool.

.jpg;maxWidth=970;quality=90)